CURATOR’S CATALOGUE TEXT – PHARMAKON EXHIBITION

Common material – perfect form – prevalence of the idea – enjoyment of the aesthetic result: the reflection of a conceptual poetic image

“I’m only saying that art is an illusion”

Marcel Duchamp

“This is not an era of finished works. It is an era of fragments.”

Marcel Duchamp

There are many fitting statements by important contemporary artists for the layered quality of the artistic output of Peggy Kliafa (1967). The French artist Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), the most disruptive artist of the 20th century said that, “Art is an illusion” and “It is an era of fragments” – both apply to both the form and the content of the Greek artist’s work. A fitting maxim is also that by Damien Hirst (1965) that “Art is like medicine. It can heal” that the British artist made in the context of his exhibition Modern Medicine in 1990, which marked the beginning of the rise of Young British Art.

In Peggy Kliafa’s art, the idea, the conceptual framework is dominant, with many connotations, simple readings and eloquent resonances. In her first solo exhibition at Kappatos Art Gallery she displays her creative output from 2008 to 2013, arranged in three sections, her years at the Athens School of Fine Arts, her graduation in 2011-2012, and the latest evolution of her work. She graduated from the Athens School of Fine Arts, 3rd Painting Workshop, directed by professor Marios Spiliopoulos, where she was also taught by professors Zafos Xagoraris and Pantelis Handris, having selected Sculpture as her main focus under professor Nikos Tranos.

The title, Pharmakon, simply and clearly encapsulates the context of her creativity with respect to the development of the idea, the medium and the base material, the aesthetic completion of her work. And this is because with each component the artist evokes and alludes to Medicine, Treatment, and Healing of body or soul.

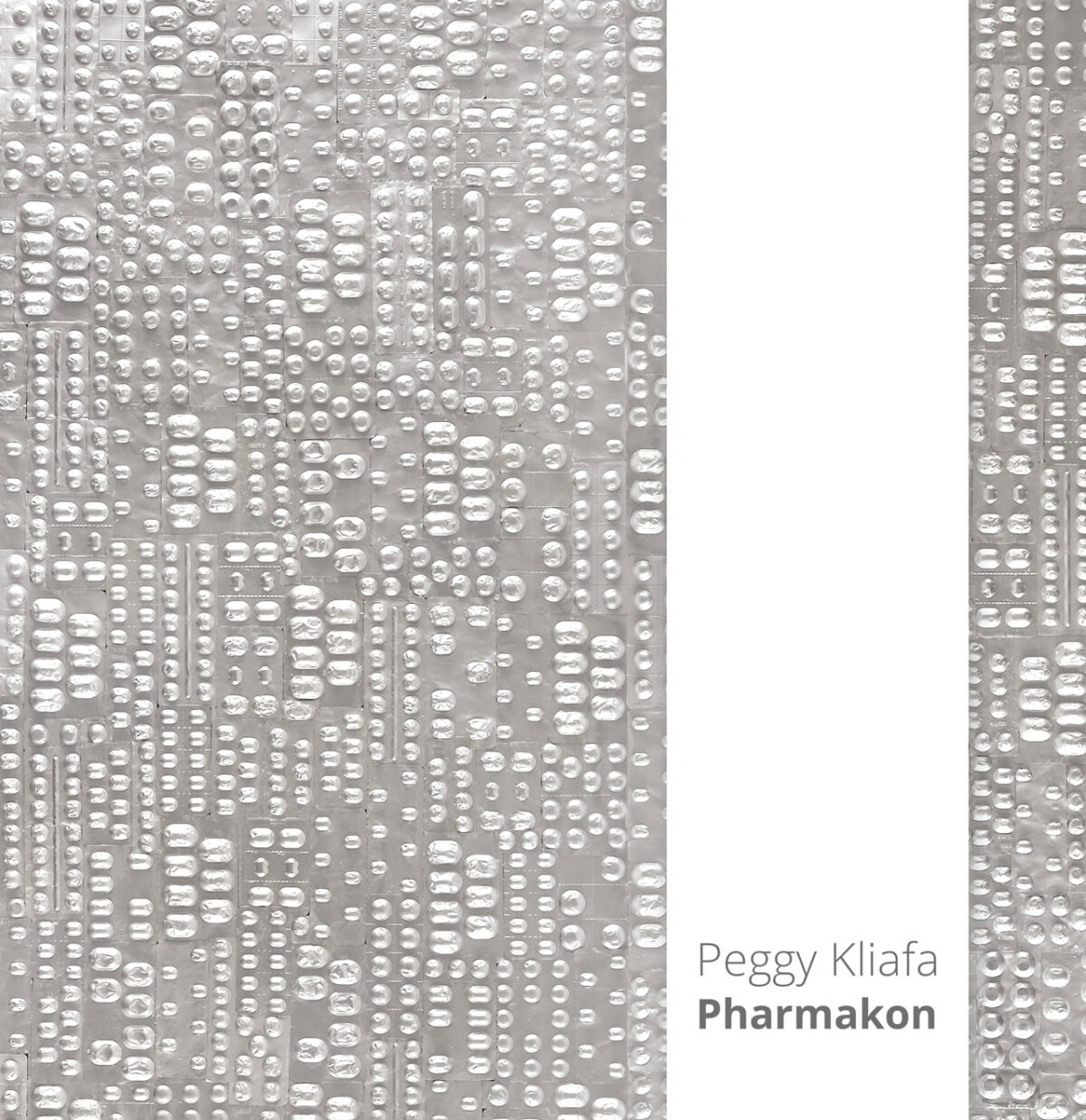

The uniqueness of her art is that she has selected as a basic, key element of her work the pill, or the blister, the medical packaging itself. Based on the pill or blister as her building block, she composes images of metal walls, stained-glass images from European cathedrals, wallpapers, lace, mosaics. Pills in different colours and shapes, and packaging, sometimes intact and sometimes used, opened, wrinkled, are arranged in geometric patterns. This new medium may be said to take the place of the brush stroke, colour, pencil, metal, glass, tessera, yarn. The strict structure, total symmetry, flawless execution, all contribute to the effect of a hallucinatory image, with a proliferation of connotations and associations.

The three sections, “Religion-Metaphysics”, “Nature”, and “Science –Chemistry”, reflect the artist’s scientific and historical research on the treatment of human disease, from primitive societies to the present day, from metaphysics and religion, the use of natural resources and herbs, and later the development of science and chemistry in the effort to heal the human soul and body. According to the artist the three sections of her work on display illustrate “the history of therapeutics as a palimpsest of metaphysics, nature and science.”

The first section, “Religion-Metaphysics”, includes works such as Vitraux and Omphalio. Harking back to European cathedrals, the Vitraux are three large-scale works that comprise the installation Remedy or Poison. The two upright works are a faithful reproduction of stained-glass windows in the Cologne Cathedral; the central Rosette comes from the Durham Cathedral. The artist believes that, “Stained-glass windows are a window to the world, in the same sense that a medicine is also a window to the world, both as a way out of illness and pain, and as worldview.” She goes on to provide a hermeneutic, psychoanalytical aspect, however: “Taking or avoiding certain medications, and the types of medication each of us takes are clear indications of our attitude to life itself.”

Omphalio, a geometric mosaic in white, yellow, red, green, and orange colours, reproduces the mosaic floor of the Sagmata Monastery in Boeotia, with squares, circles, spirals, and foliage; according to the artist, this could be symbolic of the “centre of the world”.

The second section, “Nature”, includes works such as a simple wallpaper, with the ambiguous, ironic title Nature is Innocent, which depicts images of red poppies – the opium plant – and green marijuana leaves, printed on medicine leaflets. A new work, Tree, made of effervescent tablets, is in the same section.

The third and final section, “Science – Chemistry”, comprises works made in a variety of media – paintings, sculptures, videos, reliefs, installations – including some of the artist’s oldest paintings, as well as her latest production of 2013. “Portraits of pills” depict pills as individual personalities, as celebrities, including pills of various properties and uses – antibiotics, painkillers, anti-inflammatory, or psychotropic drugs. A mosaic of pills evokes “White Lace”. The artist plays with the concepts, properties, and reception of medication and wonders: “White lace symbolizes romance, purity; it is associated with joyful events in our lives. Does this apply to medication?”

A unique work in this section is a white sculpture of a sketchily rendered human figure made of effervescent tablets; it is juxtaposed with a video playing simultaneously, dealing with the ephemeral existence of a tablet and the process of dissolving in water, which is a matter of only a few seconds.

In terms of their form, these works impress, whether they follow a process of faithful representation or develop in planes of austere surfaces, in which a simple, repetitive base pattern dominates. Thus, the Vitraux impress and mislead with the perfection of their figurative accuracy, despite the sharp contrast and challenge posed by the medium, used silver packets of pills. Works such as Armory, a huge silver wall made of the same “discontinuous” materials, astound with the power of their minimalism and the intense austerity of their conceptual potential. The work, while taking into consideration the major differences, brings to mind an environment by Jason Molfessis (1925-2009), Iron Corridor, dating from 1990 and made of heavy materials (polyester and iron), a relevant work as it, too, focuses on the power of the minimal and the beauty of the material.

Sparse works, simple assemblages, creating “metal” walls, armours, shields, columns. Powerful works, in spite of their non-figurative qualities and their emphasis on the minimal.

Peggy’s latest production of 2013 comes in continuation, but also marks an interesting evolution in both form and medium. The new, figurative works have biology as their basis, dealing with microscopic images and shapes of colonies of bacteria, their impressive formations resembling aquatic plants, corals, vegetable forms, water vortexes, brilliant formations like snow flakes, or maps. Their title, Bacteria, is a chilling reminder of their origins and functions. These new shapes, less geometric and austere, lighter, freer, more lyrical, play on the contrast of their beauty and their overt threat and lethal qualities. Regarding the medium, there is a new element here, too, as the building block in the new works is not the pill or empty packets, but smaller, lightweight items – none other than the little bits of silver paper that cover each pill.

Random influences, twists, developments often come to artists unexpectedly; what is definitely of interest is the assimilated influences, the artist’s personal expression and original proposition. Pills and medication are certainly a reference to Hirst; equally certain is the fact that the English artist always displays a mood of exhibitionism and explicit, repeated, aggressive provocation. On the contrary, Kliafa achieves a pleasant, poetic surprise in her work.

The body of her work has affinities with Minimal Art, Op Art, and of course Conceptual Art. Her art has a direct, sincere relationship with the minimal, with the common, as well as with geometric forms that are clearly defined with respect to space and viewers’ perception. She achieves the ultimate rationality of form through a systematic, laborious, and time consuming process. In her hands the common becomes powerful, invested with meaning. Peggy’s works throw into relief Adorno’s thought that art acquires meaning, significance, in the absence of function.

The visual interplay of lines, surfaces, planes, colours, where applicable, as well as the harmonious linear layout with flawless combinations of positive and negative, concave and convex, in a luminous polysemy create a visual stimulation that links the artist to Op Art. The stimulation of the gaze engenders an aesthetic interplay of light. In her works, the strictly organized groups highlight the relationship of light, shapes, and forms, resulting in a visual experience with a quality of motion and change, despite the stillness of the whole.

The mathematical structure, proportion, juxtaposition, and treatment of the building blocks of used packaging, or pills, are based on an empirical semantic system under development. Constructivist elements, combined with minimalist and conceptual loans, round off the artist’s aesthetic proposition. Yet, the manner in which the Greek artist manages her dominant influences from major movements and pursuits of 20th-century art has a certain purity in its eclecticism and a distinctively personal involvement. For instance, while remaining committed to the principle of conceptualism regarding the supremacy of content, the superiority of concept, of idea, on form, on figuration, she substantially deviates from this principle, as, even though the idea is dominant, the end result takes on an equally essential importance. The emphasis on a manual, time consuming, tedious creative process also becomes a key component in the accomplishment of her work.

The impeccable technique, application, and aesthetic effect achieve a simulacrum, a tromp l’oeil whose appeal – especially when the viewer realizes its physical nature – transcends, perhaps even confronts reality. Her works raise issues such as the ephemeral, or the relationship of high and humble art. Finally, the strong conceptual background, combined with the humble, perishable, and worthless material and the inspired execution enable aesthetic enjoyment.

The artist places importance, as we have seen, on the reception, study, and seriousness in handling the inspirations and assimilated influences that help achieve a sincere, personal proposition. The sincerity of her proposition and her commitment to making her own her primary material – pill packages or pills – draw parallels with a glorious period of contemporary Greek art – the legendary 1960s generation, which managed to be up to date with the international developments of the time and which, encouraged by avant-garde movements, expressed itself with perseverance, wisdom, and originality, each artist’s chosen medium becοming a hallmark for them. Examples include pegs, papers, affiches massicotées (shredded poster paper), plaster, weaves or clothing, trade cartons or burlap, used by Kostas Karachalios (1923), Pavlos (1930), Kaniaris (1928-2011), and Daniel (1924-2008). It is an honour for this young artist to come half a century later as a worthy continuation, proposing equally original and personal work.

Moreover, Kliafa’s works take their leads from many better- or lesser-known important artists. Suffice it to point out, from older ones, the characteristic Artériosclérose, of 1961, by Arman (1928), an assemblage with forks and spoons, or Kreis, of 1970, by Günter Uecker (1930), with its homocentric arrangement of hundreds of nails that attract and refract light in their folds, or Light Corner, of 2000, by the younger artist Carsten Höller (1961), a wall of light made up of countless bulbs.

Peggy’s Pharmakon is a brave and powerful proposition in every respect. On the conceptual and the formal plane; in execution, in completeness – and this is why the end result, after the initial surprise due to the material, inspires aesthetic enjoyment and an uplift of the soul. It is the reflection of the idea, the form and the aesthetic effect, and that is why it is fitting to cite a statement by the minimalist artist Sol LeWitt (1928-2007) that, “The idea becomes a machine that makes the art”.

Dr. Lina Tsikouta-Deimezi

Art Historian

Curator, National Gallery –

Alexandros Soutzos Museum

Translated by Dimitris Saltabassis